I’m Gillian Richmond. I’ve spent more than thirty years writing for UK stage, TV and radio. People often ask me how I got started. Welcome to part 14 of my serialized story.

Previously on This Writer’s Journey…

I’m working as a primary school teacher. The Royal Court Theatre has given me a grant to research a new play about army wives. The Ministry of Defence has arranged for me to meet a Families’ Officer somewhere on Salisbury Plain.

The Families’ Officer describes to me the army life that is embedded deep in the marrow of my bones. Nothing, it seems, has changed.

I’ve changed though. I’ve been outside army life for over a decade, navigating a path into adulthood, and haven’t spent much time reflecting on the peculiarities of my childhood. But as I drive back to London, I realise – not just in my head, but in my gut – how odd it was. As I pull up outside my flat in Hackney, the shape of a play is forming in my head. Six characters. Three soldiers, three wives. The intersecting stories of three married couples. A winner couple, a loser couple and a couple that plods along. The centre of each story will be the wife. I’m going to tell the truth of these women’s lives. The rigid ranking structures. The rumble of violence. The insecurity. The close friendships made and lost. There’s a lot to tell. I’m going to tell it all. I’ll call it The Sergeant’s Wife.

I go to my desk. I draft first an outline and then a detailed synopsis. Only when I’ve covered everything do I start to tap out the script on the clunky keys of my Commodore 64.

My life that summer is almost monastic. I write, I walk the dogs, I listen to The Archers, I watch EastEnders.

In Ambridge, Laura Archer dies. In Walford, Pauline gives birth to baby Martin.

The autumn term approaches. I finish the first draft of the play. I print it out on my dot matrix printer and give it to David to read. He has always been my biggest supporter. He goes off to read it.

When he returns he’s not smiling.

I’m sorry, he mutters. It’s a bit… He’s a kind man. He can’t go on.

He’s wrong.

Write what you know, isn’t that what they say?

I know the army life, don’t I? My play is truthful and honest and candid.

He’s wrong.

I withdraw into myself. I construct an invisible barrier down the centre of the bed. When I walk the dogs, I walk alone.

When three days have passed, I sit down and read the script again.

He’s right.

The play is boring.

I’ve thought too much, I’ve planned too much. A play should read like a living thing. This play reads like a machine. I chuck it in the bin and take the dogs out for a very long walk.

When I return home, I’ve made some critical decisions.

The play will be a two-hander. A cynical, established, thirty-ish army wife and an ingénue teenage bride will strike up an unlikely friendship. The arc of the play will follow the story of this friendship, from beginning to end.

I know these characters. I can see them in my head. I can hear them. I can practically smell their eau de cologne

I’m not going to bother with either an outline or a synopsis, I’m going to trust my gut and write what comes into my head.

Before we go on, you need to know a bit more about my Dad. Trust me on this, he’s crucial to the story of my play.

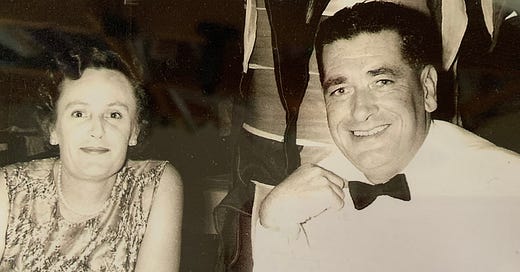

Five feet eight and a half, dark wavy hair brylcreemed back from his forehead, my father was a smart cookie. Born in the nineteen twenties, the eldest of six children raised in two rooms in a Glasgow tenement, he could weave a story from a grain of salt, and liked nothing better than to inject drama into the everyday. He was fond of Sinatra and the other crooners and was proud of his own light tenor singing voice. My first memory is sitting beside him on the stairs, while he’s hugging me and whisper-singing a Scottish folk song in my ear. As a small child I adored him.

However.

I grew up to be a bookish girl. I liked sitting in my room reading and taking the dog for long solitary walks. I liked making up poems and stories and teaching myself the guitar. I liked being alone. But my dad needed an audience for his stories. He encouraged me to invite friends home from school. And, when I did, he would elbow in and talk, talk, talk.

Yes, okay, I know, all teenagers find their parents embarrassing - but, really, he just wouldn’t stop.

My father was clear: he was the head of the household. Raised a Catholic, he was fond of the fourth commandment and as my brother and I grew older his parenting tended toward the parade ground. Even after he’d been commissioned, at home he remained the sergeant major.

As a teenager I still loved him, of course I did, but as I started to visit the homes of friends from civvy street, I glimpsed other ways of living.

One day, my Dad came home from work and announced he’d bought me a ticket to go on a Wives Club coach outing to Southampton to see Engelbert Humperdinck.

There was so much wrong with this plan that I didn’t know where to start.

I would know no one on the trip.

I was not an army wife.

The Wives Club, although theoretically open to all the wives on the camp, was the domain of the wives of the lower ranks. My father by now was a officer. Not only would there be no one else from our end of the camp, but I suspected that the women on the bus would see me as a snob - possibly even a spy.

And that’s before we even start on Engelbert Humperdinck. His real name was Gerry Dorsey and he was (still is) a crooner of sentimental ballads such as Release Me and The Last Waltz, many of them number one hits. He was enormously successful. He was not my cup of tea.

I knew I’d have to tread carefully.

My father sensed my hesitation. You’ll enjoy it, he pronounced. It’s a great opportunity.

But I don’t like Engelbert Humperdinck, I whispered.

Of course you do. The man’s a star. It’ll be good for you.

I looked to my darling mum for help.

She kept her tone gentle. How will it be good for her?

She needs to get out more. She spends too much time with her nose in a bloody book. She’s going.

My mother and I knew that tone.

I was going.

My play The Last Waltz is available as an e-book. Here’s a link.

Very moving Gillian - your early life so much of which invests your writing with its humanity.

Your post got me thinking about other films and plays about the Armed Forces. In particular The Bofors Gun, which I thought was brilliant. I think for my generation brought up on The Dambusters and Reach for the Sky, the experience of fathers in World War 2 cast a long shadow. My father was in the navy during the war and treated the household like a ship, and, at times, three sons like ratings. I was very influenced by the exceptionalism and certainty of those films. PS Thanks for your own kind comments.